Welcome to my very first blog where I discuss Cultural Anthropology in an increasingly globalized world!

As a husband and father, I find many aspects of our modern world alarming. The issues are broad and complex, from industrialization and capitalism to climate change and cultural homogeny, and we are collectively experiencing accelerated rates of change in our lives and the world. Let’s look at some of the points explored in Chapter 13 of our text, “Mirror for Humanity: A Concise Introduction to Cultural Anthropology.”

Homogenization of Culture: Modern Colonialization: as globalization increases, the more interconnected we become, the more homogenized human culture inevitably becomes. Though the idea of Cultural Imperialism, the imposition of one dominant community values over another did not enter the academic conversation until the 1960s, the historical practice is ancient and has long been connected to military conquest. The Romans enacted Pax Romana, a set of unifying laws secured through forced acculturation over diverse populations (Tobin, 2020). As homogenization increases, specific traditions, customs, and languages can quickly become threatened. “The loss of beauty” is one side of that coin; the other is the creation of new cultures, customs, languages, and traditions. New political and social units emerge but are likely temporary evolutions toward homogeny. Pidgins and Creoles are some interesting and valuable products of intercultural cross-pollination. The image below represents how many cultures embrace Western products and themes worldwide. It is essential to invest in a multi-paradigmatic approach to their study to preserve knowledge of Indigenous cultures, particularly through global, political, and social changes. As we do not exist in a mono-culture, language, religion, and technological world, we must apply multiple approaches to learning and preserving in the hopes that “Indigenous cultures are here to stay with their differences (Bahwuk, 2008).”

“Uncredited Image.” Pintrest.

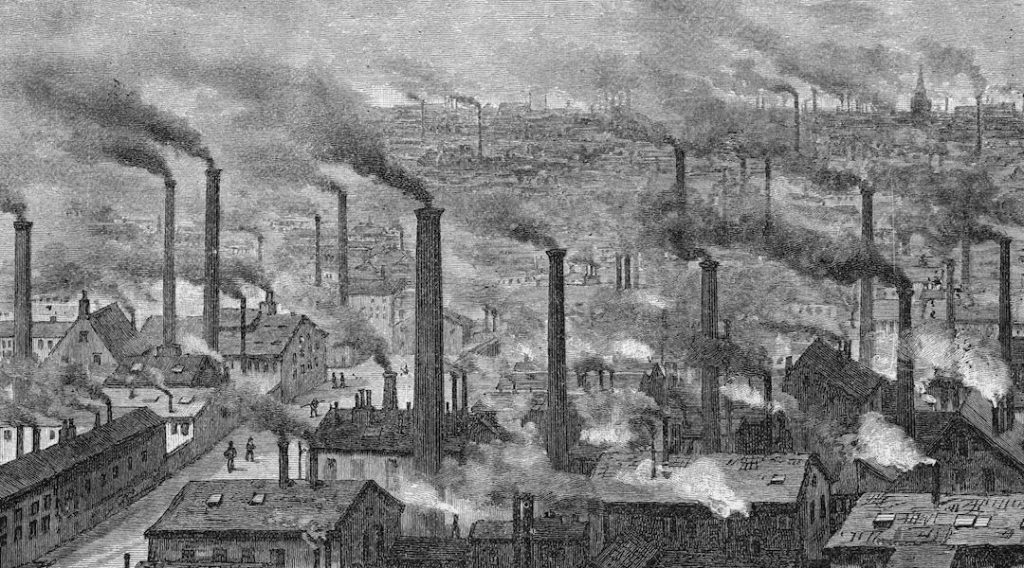

Industrial Expansion: The Western world’s industrial revolution of the last 150 years sparked a global pursuit of fossil fuels and natural resources with little to no environmental protections and guidelines. Not only has this hastened climate change, but it has allowed industry to encroach on human and animal habitats and ecosystems. Areas experiencing rapid industrial expansion often suffer similar growing pains as Victorian England during the Industrial Revolution. Workers swarm to cities looking for employment. This overwhelms underdeveloped urban housing, creating difficult, often unsafe, unsanitary conditions and leaving labor shortages in rural and agricultural communities. Poor nutrition, housing, dangerous working conditions, and sanitation contribute to workers’ stressful and unsatisfying lifestyles.

Additionally, these conditions often invite unethical employment tactics and the use of children (Kiger, 2023). Unchecked industrial expansion has dramatically impacted indigenous communities’ and populations’ social structures and designs. The damage to our environment has been devastating and is increasing as other nations pursue their industrialization. Checks and balances in industrial growth are inconsistent globally, particularly in the structure of corporations. Governments have some reciprocity to one another, but the corporate world efficiently takes advantage of loopholes in regulation. To successfully repair failed corporate control and accountability systems, “we must continue to broaden our thinking to new topics and to learn and develop new analytical tools (Jensen, 1993).” The image below is an etching of the early 1900s in Manchester, England. The Industrial Revolution started in England, where commercial steel and railroad development began.

“Uncredited Image.” The History Channel. https://www.history.com/news/second-industrial-revolution-advances

Climate Change: As the world’s industrial needs and capitalist structures grow to support demand, the human impact on the planet worsens. The retrieval of fossil fuels and scarce resources has pumped carbon into the atmosphere, raising global temperatures. Increased global temperatures strengthen all weather conditions. Tropical storms are more potent, heat waves are longer, drought conditions are extended, and flooding is worsened. Melting ice caps raise sea levels, displacing coastal communities. While some speculate upon the positive impacts of climate change- increased economic growth in some sectors and fewer deaths due to milder winters, etc., there is “overwhelming evidence that the risks and impacts from increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are very significant, will impact nearly every aspect of human life and the environment (Rising, 2022).” Climate change impacts our cultural heritages directly. Increased severity in weather patterns and rising sea levels can affect archaeological sites, artifacts, and historical structures. Indigenous communities and those living in direct connection with their natural environment are the first to suffer the effects of drought, wildfires, floods, and loss of sea ice. Ceremonial sites, traditional practices, livelihoods, and languages are all threatened by climate change (Sabushpandey, 2022).

Yuko Shimizu’s “Climate Change and the City.” YukoArt. February, 2013.

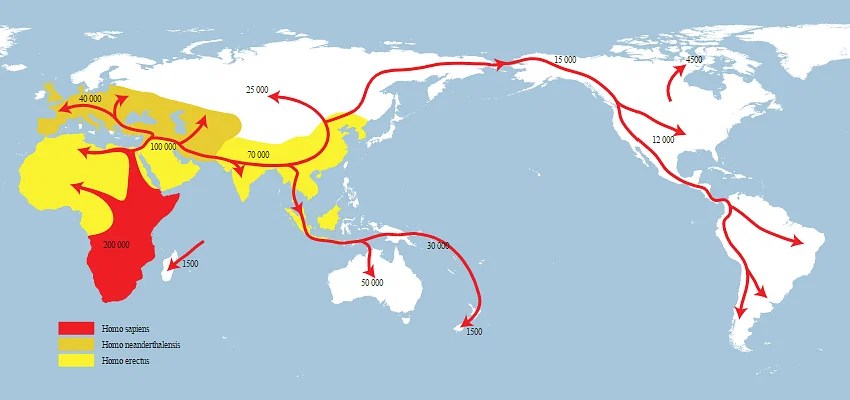

Migration, Travel, and Human Expansion: 60,000 years ago, humans began migrating from Africa and did not stop until every corner of the Earth was inhabited. As people proliferate around the globe, new cultures and customs are created. This is a testament to the need to grow, evolve, and create. As different cultures intermingle, they influence and change one another. In a perfect world, this might be seen as a positive aspect of interconnectedness, though it often leads to competition for resources, resentment, and increased xenophobia. In the long term, however, migration can lead to economic growth. For example, in 2015, “international migrants were responsible for 9.4 percent of global GDP, or more than twice what they would have produced in their home countries (NICSFG, 2021).” Migrants’ cultural mixing and remittances diversify communities, enriching them with new flavors, sounds, ideas, and perspectives. Migration has intrinsically become a culture in and of itself in our globalized reality. “Culture may also serve as a crucial means for empowerment and self-expression for migrants and refugees during their journeys, including in situations of trauma and loss. The ability to practice one’s faith, to express oneself through music, poetry, theatre, or cooking, and offer critical support to migrants and refugees as they build new lives and homes while seeking a common sense of humanity with the societies to which they move (Megha, 2016).”

Map of Homo Sapiens Migration. Public Domain.

Indigenous Rights and Eradication: Generally vulnerable, Indigenous people have historically been displaced, impoverished, and oppressed. This issue combines human expansion and capitalism as issues that impede Indigenous peoples around the world, who have many times been the targets of genocide. “International law defines genocide in terms of violence committed “with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group,” yet this approach fails to acknowledge the full impacts of cultural destruction (Kingston, 2015).” In the fight to protect and maintain land and resources, these communities are often outmatched by more powerful and wealthy governments and corporations. Indigenous resilience is remarkable, considering outside elements’ consistent pressure and efforts to take their land. Indigenous rights organizations work to help protect these lands and resources. When Indigenous rights are protected, languages, practices, and traditions are preserved and sometimes revitalized. Without protection, we lose connection to ancestral lands, resources, and strong cultural identity through assimilation. Constant contests by governments and corporations over land rights weaken Indigenous community’s connection to their ancestral and spiritual environment, traditional land use, and management.

Blackbear Bosin, “Trail of Tears”/Denver Post/Getty Images

Westernization and Post-Modernity: The omnipresent influence of Western culture is eroding cultural diversity globally. Cultural Imperialism and colonialization contribute by imposing foreign culture on encroached communities and societies. Westernization indicates the influence of pop culture in language, fashion, music, and entertainment on non-Western society. Modernity implies technological and industrial evolution not specific to a region. Western cultures often celebrate individualism over collectivism, which clashes with many non-Western collectivist cultures. This can impact family, kinship, and community cultural structures. Westernization and modernization also bring about changes industrially and socially, as well as increased urbanization, literacy, and changing gender roles, which can challenge many cultural and social norms. This can be resisted, but with fast-growing and spreading technology and media, people exposed to new or modern cultural mores often desire the new customs, cultures, and material over their own, bringing a social skepticism that is an earmark of Post-Modernism. This post-modern rejection of ‘what was’ contributes to the erosion of cultural identity.

Uncredited Google Image

Disease: As the world becomes more interconnected and interdependent, and as communities and regions become literally and figuratively ‘closer,’ the opportunities for diseases and pathogens, once separated geographically, to spread increases. Zoonotic diseases are the most prevalent example of this. Infectious agents specific to humans have been widely spread, but as the global economy intermeshes, Zoonotic diseases are spreading with increasing frequency, as the COVID-19 pandemic showed us firsthand. Sadly, efforts to track and identify new contagious pathogens are often underfunded and supported, and occasionally, as with the PREDICT project, shut down by ignorant, isolationist, and self-interested Presidents. Which raises “serious concern for public health and leaves nations with the task of determining the infectious agents that have the greatest potential to establish within their borders (Smith, 2007).” Different cultures have social and sanitation norms and standards that can inhibit or encourage the spread of disease. Hindus bathe in and drink the polluted water of the Ganges, believing that its spiritual powers protect them from illness and bless them. Some cultures and religions eschew vaccines, medicine, and medical intervention, and these cultural differences can impact the transmission of disease. The way the different cultures gather and socialize impact transmission, “directly transmitted infections, pathogen transmission relies on human-to-human contact, with kinship, household, and societal structures shaping contact patterns (Buckee, 2021).”

Ebola Victim. Photo by Jerome Delay, AP.

Indigenous Resilience and Local Autonomy: This is an interesting clash of identities. Modern global capitalists vs. local ecosystems: people, plants, and animals. Corporations need to be pushed to use environmentally friendly and socially responsible policies. Indigenous people and communities need to be free to honor traditions and customs. They also need the resources to survive and thrive while protecting flora and fauna. It is a balancing act, and often, the Indigenous people are the ones who get the short end of the stick.

Additionally, Indigenous peoples are consistently vulnerable globally to black market and criminal activity. Drug trafficking and rebel factions often invade protected territory with little governmentally imposed consequences throughout Latin and South America, Africa, and Asia. While “village-level indigenous customary laws and traditions can be invaluable institutional instruments for the provision of public goods, they are insufficient (Ley, 2019).”

Uncredited Image from

Carlos Mamani Condori’s Indigenous Peoples and the Right to Self-Determination

Capitalism, Consumption, and Materialism: Capitalism is an economic system, but consumption and materialism are socialized belief structures. They are connected but conceptually independent ideas. The drive to produce cheap products for mass consumption increases industrial footprints and exacerbates the wealth gap. Western manufacturing has moved factories and production to places that offer cheap labor, often marginalized and vulnerable people and places. Job opportunities encourage migration, which disrupts communities and populations and increases risks, such as the spread of disease. But perhaps there is an even darker human emotional aspect of rampant consumption. In her paper, The Age of Consumer Capitalism, Paula Cerni argues that “the endless construction of identities and desires, disconnected from the material power to shape society according to human designs, will always feel somewhat inauthentic because it is. For every construction, there is a deconstruction; every choice is unconnected and irrelevant to the next one; and the proliferation and commercialization of meanings expose the lack of common purpose at the heart of our society (Cerni, 2007, p. 22)” hastening cultural meaninglessness or nihilism.

Uncredited Image from

Yasmine Modaresi’s The Consumerism Trap: The Social, Financial, and Environmental Destructiveness of Over-Consumption. Medium. March, 2022.

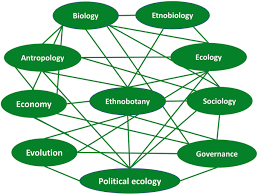

Evolution of Ethnoecology and Ecological Anthropology: As the landscape of our physical and social world continues to change with the cross-pollination of people and culture, so does the study of it. Technology, the changing climate, resources, and political and religious influence all impact and change ecosystems and social systems, people’s perceptions, and participation within culture. There is no ‘one evolutionary path’ for humans. Each culture and people adapt to their specific environment. As social and environmental issues change and evolve, so do our adaptations. In another of his papers, Conrad Kottak, the author of our textbook, explains that new ecological anthropology “is located at the intersection of global, national, regional, and local systems, studying the outcome of the interaction of multiple levels and multiple factors” blending theoretical and empirical research with applied, policy-directed, and critical work (Kottack, 1999).

Uncredited Image from

Alejandro Casa’s Perspectives of the Ethnobotanical Research in Mexico. Springer Nature. University of Virginia Library. June, 2023.

Sources:

Bhawuk, Dharma P.S. Globalisation and Indigenous Cultures: Homogenization or Differentiation? International Journal of Intercultural Relations. Vol 32, Issue 4, July 2008.

Buckee, Caroline. et al. Thinking Clearly About Social Aspects of Infectious Disease Transmission. Nature. June, 2021.

Casa, Alejandro. et al. Perspectives of the Ethnobotanical Research in Mexico. Springer Nature. University of Virginia Library. June, 2023.

Cerna, Paula. The Age of Consumer Capitalism. Paula Cerni and Cultural Logic, 2007. Pp. 1-28.

Condori, Carlos Mamani. Indigenous Peoples and the Right to Self-Determination. Cultural Survival. April, 2024.

Groeneveld, Emma. Early Human Migration. World History Encyclopedia, May, 2017.

Jensen, Micheal C. The Modern Industrial Revolution, Exit, and the Failure of Internal Control Systems. The Journal of The American Finance Association. Vol 48, Issue 3, July 1993.

Kiger, Patrick J. 7 Negative Effects of the Industrial Revolution. History.com.

Kingston, Lindsey. The Destruction of Identity: Cultural Genocide and Indigenous Peoples. Journal of Human Rights. January, 2015.

Kottak, Conrad P. Mirror for Humanity: A Concise Introduction to Cultural Anthropology 13th Ed. University of Michigan. McGraw Hill. 2023.

Kottak, Conrad P. The New Ecological Anthropology. American Anthropologist. March 1999.

Ley, Sandra. et al. Indigenous Resistance to Criminal Governance: Why Regional Ethnic Autonomy Institutions Protect Communities from Narco Rule in Mexico. Latin American Research Review. Cambridge University Press. April, 2019.

Megha, Amrith. Migration and the Power of Culture. United Nations University. September, 2016.

Modaresi, Yasmine. The Consumerism Trap: The Social, Financial, and Environmental Destructiveness of Over-Consumption. Medium. March, 2022.

National Intelligence Council’s Strategic Futures Group (NICSFG). Global Trends, the Future of Migration. The National Intelligence Council. March, 2021.

Rising, James. et al. The Missing Risks of Climate Change. Nature. October 2022.

Sabushpandey. Climate Change and the Loss of Culture: Why You Should Care. The Bard Center for Environmental Protection. May, 2022.

Smith, Katherine F. et al. Globalization of Human Infectious Disease. Ecology. August, 2007.

Tobin, Theresa Weynand. Cultural Imperialism”. Encyclopedia Britannica. May, 2020.

Leave a comment